Intern Writer, Sam E. Rubin

[A young white male (Sam E. Rubin) dressed in a dark shirt, wearing glasses, and holding an award at the LA FILM FESTIVAL, 2009.]

My name is Sam E. Rubin. I am a singer, actor, filmmaker, and ambassador for Lights! Camera! Access! (LCA). As someone from the neurodivergent community, I would like to share a story about threading the needle of my disability to success.

As a child, I had typical development, then regressed around age three and a half. To illustrate this point, my mother tells a story of playing a musical game with me before I received the diagnosis of autism. I loved music. I wanted to hear Paganini. But she couldn’t find the CD. So, thinking to herself, “He’s just a toddler; what does he know?” she put on something else. I remember the moment. The crushing disappointment. I burst into tears, “That’s not Paganini!” I said, “That’s Wieniawski’s ‘Caprice in A Minor’!” Shortly after that, I lost all my language development and social skills. I was silent for fourteen months and subsequently diagnosed with autism. This changed everything. I was thrust into special education. But music has always been a way for me to connect socially.

Even though it took many years for conversational talking to come back together, I could always sing. In second grade, I tried out for a boychoir and got in. Because I have perfect pitch, I was able to sing well. But I held the music upside down, frustrating the choirmaster. He didn’t understand that once I hear music, it’s in my head like a tape recording. I didn’t need to read or even look at the music to stay on pitch or harmonize. However, there are social conventions to singing in a Boychoir: holding still and holding one’s music were two challenges for me. I did get the “holding still” part down. But I was left behind because my music was often upside-down. It was the first of many similar painful experiences of being left out. Birthday parties were another occasion to disinclude the kid with autism.

Probably the most uncomfortable thing about having an autism diagnosis is that people are fearful of you and dismissive. I am generally optimistic and earnest. My friends call me the “walking talking Sponge Bob.” I like that description because I am friendly. But social navigation is filled with unspoken rules and with social opportunities, it’s easier to learn the ways of social communication.

Attending school was a disaster. My parents tried everything from special ed to regular school with an aide to private school. At the end of fifth grade, when I was functionally illiterate, and they were still planning to pass me up to grade six, my parents decided to homeschool me. This was a lucky break because my mother was creative in getting me back up to speed with reading and math. She also got me into learning environments that supported my interests. Not being “in” school gave me time for these fantastic learning situations, which have shaped my life and career.

Since my dad specialized in video production, I have constantly been exposed to cameras and editing equipment. My very first film, at age nine, was Nosferatu-inspired. My parents had taken me to a cosplay event for F.W. Murnau’s film Nosferatu, where people came dressed up as characters from the film, and the music was played live by an in-person accordionist. How exciting! When I got home, I improvised music for my own Nosferatu film called Werewolf 1991, set in the Silent Era. Because of this first film, my parents enrolled me in a terrific program called San Francisco Art&Film for Teens. This marked the beginning of my film, history, and art education and of making more films.

Some of the films I made got into top festivals. At age 15, I won Target’s “Dream in Color” Award for directing at the Los Angeles Film Festival for my student film, Lipstick, about a boy who experiments with his sexual identity. This program was a staple of my education during junior high and high school. In class, we would watch an old film that had historical significance. The film mentor—Ronald Chase—would elaborate on it. And then, he asked us to write about what we had learned. My mother used these writings for my English composition assignments.

I eventually started my own film club at an art gallery in Berkeley, California. The format was a cartoon or short film related to the film; I’d introduce the film and show it. Afterward, I held an impromptu discussion about the film. This experience taught me how to speak informally (unscripted) to an audience.

Recently, I attended a performance with my former mime teacher where he wore a mask that looked “mad/angry.” He asked the audience to notice if the expression on the mask changed due to his body language. It did! I could see it! As if by magic, the angry expression on the mask vanished. The character he played showed many expressions of moods ranging from complacent to sad. I probably could not have seen that when I was a kid. But I can see it now. There is so much to language that is non-verbal and gestural. It’s generally assumed that kids pick up on this stuff by being together. That is not easy for someone with autism.

Because of the delayed language barrier for so long, my mother enrolled me in an acting camp when I was nine, which helped me develop social conversation skills. Kid A says a line; Kid B responds, and, like ping pong, a conversation happens. It ended up being a blessing in disguise. Not only did I learn the skill of dialoguing, but my inner thespian was released. Luckily, shortly after that, I was cast as Tiny Tim in A Christmas Carol at Contra Costa Community College in Richmond, California. Being on stage was the first time I felt comfortable in a social situation. I remained involved in acting (both in theater and film) throughout junior high and high school. This led me to meet my music mentor—Peter Maleitzke, former artistic director of American Conservatory Theater—with whom I still study Bel Canto singing. Thanks to Peter’s influence (I don’t hold my music upside-down anymore!) I have sung with Pocket Opera in the San Francisco Bay Area for five seasons.

I was accepted into the Tom Todoroff Studio Acting Conservatory in New York City, where I studied for two years. Living independently in the Big Apple was a huge growth experience, and I loved every minute of it! When I returned from the acting conservatory in NYC, I stumbled upon Lights! Camera! Access! (LCA) I performed in a staged reading called “A Day On the Road to ADA,” where I played Congressman Tony Coehlo, one of the founders of the Americans with Disabilities Act.

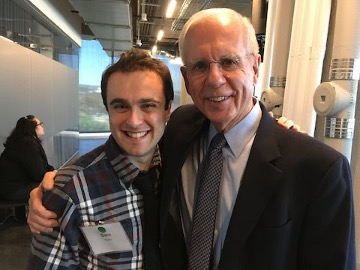

[Description: Two white men (Sam E. Rubin and Representative Tony Coehlo, author of the Americans with Disabilities Act) hug shoulder to shoulder.]

[Image description: A line of actors with various disabilities sit on a stage for a staged reading of One Day On the Road to the ADA.]

Then, the pandemic hit! I could not get back to NYC to continue my career. Throughout this historical moment, I’ve kept up with Lights! Camera! Access! and have grown in my understanding of disability advocacy and inclusion in the arts. I don’t think this would have happened had the pandemic not intervened.

This past holiday season, I was a disability consultant for Inclusive Arts for American Conservatory Theater’s first-ever “sensory-friendly” production of A Christmas Carol. What a joy to be part of offering live theater to those who would normally be excluded.

LCA has been invaluable in learning to be an inclusion advocate—recognizing that people are different and the same is a superpower. Whereas, before, I found myself locked into the game of trying to pass as “normal” (whatever that is!), now I believe that there is a place for talented and disciplined people with disabilities to shine in the world of the arts without having to pretend to be someone they are not. I recently read Big Magic by Elizabeth Gilbert. She used an expression—the arrogance of belonging—to mean including oneself in the group even where one does not feel a part of it. I like this expression. It effectively encapsulates what it is to invite oneself to participate in the normative/ableist world without sacrificing one’s true identity.

The practice of caring, too, so fundamental to inclusion, is a skill that is not normally taught in a world in which competition reigns supreme. As an actor, opera singer, director, and someone who has lived with autism, I do compete in the world, and I am proud of my accomplishments. The autism experience is my superpower. Because of this, I don’t take my blessings and abilities for granted. I can help bolster others with disabilities to encourage them to shine.

I joined the Lights! Camera! Access! (LCA) Newsletter/Marketing team because of its mandate for inclusion in the arts. My experience can be helpful to others who are finding their way in their careers.

About the Author: Sam E. Rubin is a contributing Inter Writer – with Lights! Camera! Access! (LCA) Newsletter/Marketing Team. He joined the disability newsletter brand in 2023. When he is not acting or creating films, Sam is also involved in advocacy.

[A Caucasian man (Sam E. Rubin) is dressed in a dark shirt, and smiles to the camera.]

Contact Information:

Website: Sam Rubin Actor

YouTube: Sam Rubin (YT)

Facebook: Sam E. Rubin (FB)

IG: Sam Rubin (IG)